Accumulators and Lehman Brothers Minibonds: Know the products, know your rights

24Jan2015Recently there has been a lot of discussion among legislators, regulators and investors concerning the mis-selling of accumulators and Lehman Brothers Minibonds. Since the fall of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, many investors, be they individual or institutional, have suffered huge losses from their investments, particularly those who bought high-risk products. In this article, we hope to give you an overview of the nature of certain topical financial products, and discuss issues that investors should consider before committing themselves in financial transactions.

What is an Accumulator?

Accumulators are structured financial products. By entering into an Accumulator contract, you are agreeing to purchase a fixed amount of security, commodity or currency from a bank on a daily basis at a predetermined price (“Strike Price“). The contract usually lasts for a year, ie 250 trading days.

The Strike Price is set at a specified percentage of the initial market price of the stocks (“Initial Spot Price“) so as to enable buyers to accumulate stocks at a discount. If the price of the stocks rises to 3%- 5% above the Initial Spot Price, the contract will be knocked out and the investor is under no obligation to perform the contract. However, if the price of the stocks goes below the Strike Price, the contract will continue and investors are obliged to keep accumulating stocks, notwithstanding that they are buying them at a loss.

After the crash of worldwide stock markets, the prices of many stocks reached their lowest, and it became unlikely that the stock prices would rise to a level that would trigger a knock-out before the expiry of the accumulator contracts. Thus some investors chose to unwind their accumulator contracts to cut losses, which inevitably attracted a significant penalty.

Accumulators are very risky products. The investor’s gain is capped at a certain level but the extent of his losses is not limited. The downside risk seems remote when the market is good, but once the risk is realised the consequences can be disastrous. This is especially so for investors who leveraged their accumulator contracts on margin; these investors ended up losing all their money and owing large sums of money to banks.

What are Minibonds?

Since 2002, Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc (“Lehman Brothers”) had been issuing a structured product called “Minibonds”. To the surprise of many investors, a Minibond is not a bond issued by Lehman Brothers or any governmental body. It is a high-risk credit-linked note linked to an underlying security. It guarantees investors some payment of interest at regular intervals, which makes it looks like a bond.

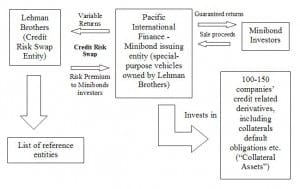

Since the structure of Minibonds is complicated, the following diagram may help illustrate how one series of Minibonds works:

The Minibonds were issued through a special purpose vehicle called Pacific International Finance (“PIF“). PIF was a wholly owned subsidiary of Lehman Brothers.

Lehman Brothers, being the issuing bank in this case, might or might not have invested in the companies on a list of reference entities. The list of reference entities consisted of sizeable and reputable companies, and they were simply used as a “reference” for credit default event purposes. Assuming that Lehman Brothers invested in the stock of some of these reference entities, inevitably Lehman Brothers exposed itself to a degree of risk. To minimise the risk, Lehman Brothers tried to buy “insurance” from retail investors through issuing the Minibonds.

Investors of the Minibonds paid money to PIF in exchange for Minibonds coupons. PIF, which collected investors’ money via various distributing banks, invested the money in the credit-related derivatives of 100 to 150 companies (“Collateral Assets“), some of which were collateral debt obligations (“CDOs“) involving sub-prime debts. In return, PIF guaranteed the Minibonds investors that they would get a fixed return of about 5% on their investments (“guaranteed return“).

In reality, the return on the CDOs was a variable one, which means that PIF’s investment in the CDOs might exceed 5%. In that case, PIF might keep the excess after paying 5% to the Minibond investors. Therefore, it was likely that PIF would choose to put their money in risky investments which gave returns higher than 5%, which in turn enabled them to gain from the arrangement.

To insure itself against the risk of exposure to the reference entities, Lehman Brothers swapped its risk against the reference entities with PIF, whose risks were the variable return from the CDOs. In return for this swap, Lehman Brothers agreed to give a premium at around 5% to PIF, which was then given to the Minibond investors. By accepting this 5% of return, Minibond investors were effectively giving “insurance” to Lehman Brothers insuring them against its risks. But Lehman Brothers did not insure Minibond investors against the failure of the Collateral Assets or the CDOs at any point of time. This was the “Credit Swap Arrangement”.

Under the Credit Swap Arrangement, once a credit event happened, the arrangement came to an end and the Minibonds were liquidated. Credit Events include:

- If any of the reference entities failed, investors would have to pay Lehman Brothers for the “insurance” it had bought via the Credit Risks Swap.

- If more than 11 companies of the 150 companies listed in the Collateral Assets failed, or a certain percentage of the CDOs or credit linked derivatives held as Collateral Assets went into default, the whole Minibond would be liquidated, and the loss would be borne by investors.

In scenario 1, investors could lose their money as they had insured Lehman Brothers against the risks of the reference entities. The amount of loss would be heavily dependent on the recovery rate of the failed entities. In scenario 2, since the Minibonds would be liquidated, investors who held Minibond coupons would be unable to get any further return from the CDOs. PIF bore no risk of default in the whole arrangement.

Contractually, the fall of Lehman Brothers is not one of the credit events. However, the winding up of Lehman Brothers halted the payment of the 5% premium to investors. Further, as investors’ money had all gone to the CDOs and Collateral Assets, the fall of Lehman Brothers significantly diminished the value of those CDOs. In some cases, the value of the investments became almost worthless.

When the crisis unfolded, many investors filed complaints to the Securities and Futures Commission (“SFC“) and the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (“HKMA“), alleging that the retail banks had mis-sold the Minibonds to them. Indeed, the incident has raised a number of important issues. First, it is questionable whether the distributing bank clearly described and explained the products to Minibond investors. As the product was so complicated, even sales representatives at banks did not fully understand the underlying risks, and it is therefore unlikely that they accurately communicated the risks to retail investors.

Further, it appears to be misleading to call, or to allow this product to be called, a Minibond. Generally, bonds are low risk in nature and the yield is stable and guaranteed, yet Minibonds are nothing like real bonds except that they yield a fixed premium at intervals.

Who are Professional Investors?

Under the Securities and Futures Ordinance (Cap. 571) (“SFO“), any person or corporation who satisfies the requirements set out in Part 1 of Schedule 1 and section 3 of the Securities and Futures (Professional Investors) Rules is deemed to be a “Professional Investor”. According to the sections, the following parties are covered:

- A trust corporation which has total assets of not less than $HK40 million;

- Any individual, either alone or with any of his associates on joint account, having an investment portfolio of not less than HK$8 million;

- Any corporation or partnership having a portfolio or not less than HK$8 million or total assets of not less than HK$40 million; and

- Any corporation whose sole business is to hold investments and which is wholly owned by an individual who, either alone or with any of his associates on a joined account, has an investment portfolio of not less than HK$8 million.

When dealing with Professional Investors, financial institutions or banks are exempted from certain prohibitions, namely:

- From issuing any advertisement, invitation or document made in respect of securities, or interests in any collective investment scheme or regulated investment agreement, which are or are intended to be disposed of only to Professional Investors (SFO s.103 (3)(k));

- From making unsolicited calls (“cold calls”) in respect of marketing investment products (SFO s. 174(2));

- From Communicating an offer to acquire or dispose of any securities issued by a body but not accompanied by a written document that contains all the necessary information on the offer (SFO s.175).

In this regard, it appears that the word “Professional” points only to the state of wealth of an individual, rather then his state of knowledge. This is, of course, nonsense. Having a certain net worth does not mean a person is sophisticated or knowledgeable enough to safeguard his own interests and make the most suitable investment decisions. On the contrary, some “Professional Investors” may be more vulnerable than average investors as they are entitled to less protection under the law. As financial markets have developed very quickly, banks have designed and marketed many types of structured products in order to attract more funds from investors. Investors are expected to keep abreast of the developments in financial markets so that they clearly understand the products that they are investing in.

What is the effect of signing a Notice to Professional Investors?

According to 15.4 of the Code of Conduct for Persons Licensed by or Registered with the Securities and Futures Commission (“Code of Conduct“), financial institutions and banks must provide a written explanation to clients explaining the risks and consequences of being treated as a Professional Investor. If a client is classified as a Professional Investor, the bank will ask the client whether he wishes to sign the Notice to Professional Investors (the “Notice“), which waives certain obligations of the bank. The purpose of this Notice is to ensure the investor consents to become a Professional Investor and acknowledges that he understands what information will not be provided to him.

If an investor agrees to be treated as a Professional Investor, the bank is not required to enter into a written agreement with him or to provide him with any written risk-disclosure statements. Further, the bank is not obliged to advise Professional Investors about the suitability of any recommendations put forward by it, or to provide prompt confirmation about the essential features of any transactions effected. Details of the exemptions are usually set out in the Notice.

The relaxed compliance requirements on banks give Professional Investors more flexibility in day-to-day trading, but fewer protections under the Securities and Futures Ordinance. However, under section 15.3 of the Code of Conduct for Persons Licensed by or Registered with the Securities and Futures Commission, financial institutions are advised to assess whether a person has sufficient knowledge in the financial market or expertise in relevant products to qualify as a Professional Investor. According to the Code of Conduct, banks should take into account the following matters:

- What did the investors trade before? What type of products has the person traded?

- The size and the frequency of his trades (Professional Investors would be expected to have entered into not less than 40 transactions per year);

- Dealing experience (a Professional Investor should have been active in the relevant market for at least 2 years); and

- Awareness of the risks involved in trading in the relevant market.

Do aggrieved Professional Investors have any recourse for mis-selling?

After the collapse of Lehman Brothers, investors who purchased Minibonds started a series of demonstrations and filed complaints with the HKMA and the SFC, urging the authorities to investigate the whole affair. As mis-selling financial products is regulatory misconduct, the SFC commenced investigations which are expected to last for a considerable period of time. However, even if banks are found to have mis-sold Minibonds or other structured products, investors will not receive monetary compensation.

In order to obtain remedies from the banks, investors can commence lawsuits on the grounds of misrepresentation and/or negligence. The chance of success would very much depend on the factual circumstances of each case and the background of the claimant. Needless to say, if the SFC has found misconduct on the part of the bank, it will definitely assist the investors’ civil claim. Further, investors are entitled to request tapes of telephone conversations with the bank, and ask for copies of the sales documents that they have signed. This type of evidence is always useful.

What duties do financial intuitions or banks owe to investors under the common law?

Although financial institutions and banks are exempt from certain compliance measures when dealing with Professional Investors, they do owe a duty of care to this special group of clients under the common law.

It is established law from the leading Hong Kong case Field v Barber Asia (where this firm acted for the successful plaintiff) that financial advisers are liable for damages for any negligent advice given to their investors. A summary of the case can be found here.

Following this case, it is clear that the burden is upon financial advisors to ensure that products introduced by them heed the real desire and risk appetite of investors. Investment advisers should adequately explain the risk to investors and ensure that they understand them. This is so even when investment advisers have complied with all the regulatory rules and investors have signed all the application forms, explanatory documents, declarations and risk-disclosure statements.

An investor should establish that: (i) he is an inexperienced investor who has little knowledge about the financial market; (ii) the bank is acting in the capacity of a financial advisor and not merely a salesperson; (iii) the financial advisor in question has failed to take into account the investor’s risk appetite when entering into financial transactions, and (iv) the risks were not clearly explained or disclosed to the investor prior to his entering into the transaction. Apart from these, the Court will also consider other relevant circumstantial factors of each case.

Focusing on the issues of risk disclosure, some argue that Lehman Brothers have done their job in that investors were provided with a prospectus which set out the Credit Swap Default and the criteria for choosing suitable Collateral Assets. However, the truth is that the composition of the Collateral Assets was never listed out in the Minibond prospectus, which suggests that investors were not told into which entities they were putting their investment money before they bought the Minibonds. According to the Prospectus, “We cannot state with certainty what the collateral will be when we publish an issue prospectus for a series of notes as we rely on the arranger to make suitable collateral available to us.”

This article is not legal advice. You should seek professional advice before taking any action based on the content of this article.

If you would like to discuss any of the matters raised in this article, please contact:

| Ian De Witt Partner | E-mail | Robin Darton Partner | E-mail | Sunny Hathiramani Partner | E-mail | Troy Greig Partner | E-mail |

Disclaimer: This publication is general in nature and is not intended to constitute legal advice. You should seek professional advice before taking any action in relation to the matters dealt with in this publication.